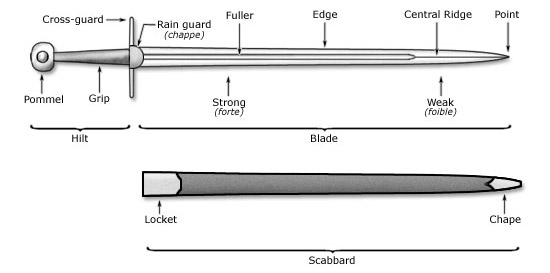

Anatomy Of A Sword

The sword consists of the blade and the hilt. The term scabbard applies to the case that covers the sword blade when not in use.

Blade

Three types of attacks can be performed with the blade: striking, cutting, and thrusting. The blade can be double-edged or single-edged, the latter often having a secondary "false edge" near the tip. When handling the sword, the long or true edge is the one used for straight cuts or strikes, while the short or false edge is the one used for backhand strikes. Some hilt designs define which edge is the 'long' one, while more symmetrical designs allow the long and short edges to be inverted by turning the sword.

The blade may have grooves known as fullers for lightening and stiffening the blade while allowing it to retain its strength, similar to the structure of a steel "I" beam used in construction. The blade may taper more or less sharply towards a point, used for thrusting. The part of the blade between the Center of Percussion (CoP) and the point is called the foible (weak) of the blade, and that between the Center of Balance (CoB) and the hilt is the forte (strong). The section in between the CoP and the CoB is the middle. The ricasso or shoulder identifies a short section of blade immediately forward of the guard that is left completely unsharpened, and can be gripped with a finger to increase tip control. Many swords have no ricasso. On some large weapons, such as the German Zweihänder, a leather cover surrounded the ricasso, and a swordsman might grip it in one hand to wield the weapon more easily in close-quarter combat. The ricasso normally bears the maker's mark. On Japanese blades this mark appears on the tang (part of the blade that extends into the hilt) under the grip.

- In the case of a rat-tail tang, the maker welds a thin rod to the end of the blade at the crossguard; this rod goes through the grip (in 20th-century and later construction). This occurs most commonly in decorative replicas, or cheap sword-like objects. Traditional sword-making does not use this construction method, which does not serve for traditional sword usage as the sword can easily break at the welding point.

- In traditional construction, the swordsmith forged the tang as a part of the sword rather than welding it on. Traditional tangs go through the grip: this gives much more durability than a rat-tail tang. Swordsmiths peened such tangs over the end of the pommel, or occasionally welded the hilt furniture to the tang and threaded the end for screwing on a pommel. This style is often referred to as a "narrow" or "hidden" tang. Modern, less traditional, replicas often feature a threaded pommel or a pommel nut which holds the hilt together and allows dismantling.

- In a "full" tang (most commonly used in knives and machetes), the tang has about the same width as the blade, and is generally the same shape as the grip. In European or Asian swords sold today, many advertised "full" tangs may actually involve a forged rat-tail tang.

From the 18th century onwards, swords intended for slashing, i.e., with blades ground to a sharpened edge, have been curved with the radius of curvature equal to the distance from the swordman's body at which it was to be used. This allowed the blade to have a sawing effect rather than simply delivering a heavy cut. European swords, intended for use at arm's length, had a radius of curvature of around a meter. Middle Eastern swords, intended for use with the arm bent, had a smaller radius.

Hilt

The hilt is the collective term of the parts allowing the handling and control of the blade, consisting of the grip, the pommel, and a simple or elaborate guard, which in post-Viking Age swords could consist of only a crossguard (called cruciform hilt). The pommel, in addition to improving the sword's balance and grip, can also be used as a blunt instrument at close range. It may also have a tassel or sword knot.

The tang consists of the extension of the blade structure through the hilt.

Source: Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia